What is a Cell?

Cell

Smallest structural and functional unit that exists independently and performs all vital life functions.

Organisms may be unicellular—one cell handles all tasks—or multicellular, where many specialised cells cooperate.

Can something lacking all life functions still be called a cell? Explain.

Birth of Cell Theory

Trace the journey from early microscopes to Virchow’s dictum, Omnis cellula e cellula — every cell comes from a pre-existing cell.

17th-Century Microscopy

Hooke names “cells” in cork (1665); Leeuwenhoek observes living cells, launching cell history.

Schleiden & Schwann (1838–39)

They propose all plants and animals are built of cells, unifying biology under one principle.

Virchow (1855)

Observes cell division and states Omnis cellula e cellula, cementing continuity in modern cell theory.

Pro Tip:

Remember the sequence: Hooke → Schleiden & Schwann → Virchow to recount the birth of modern cell theory.

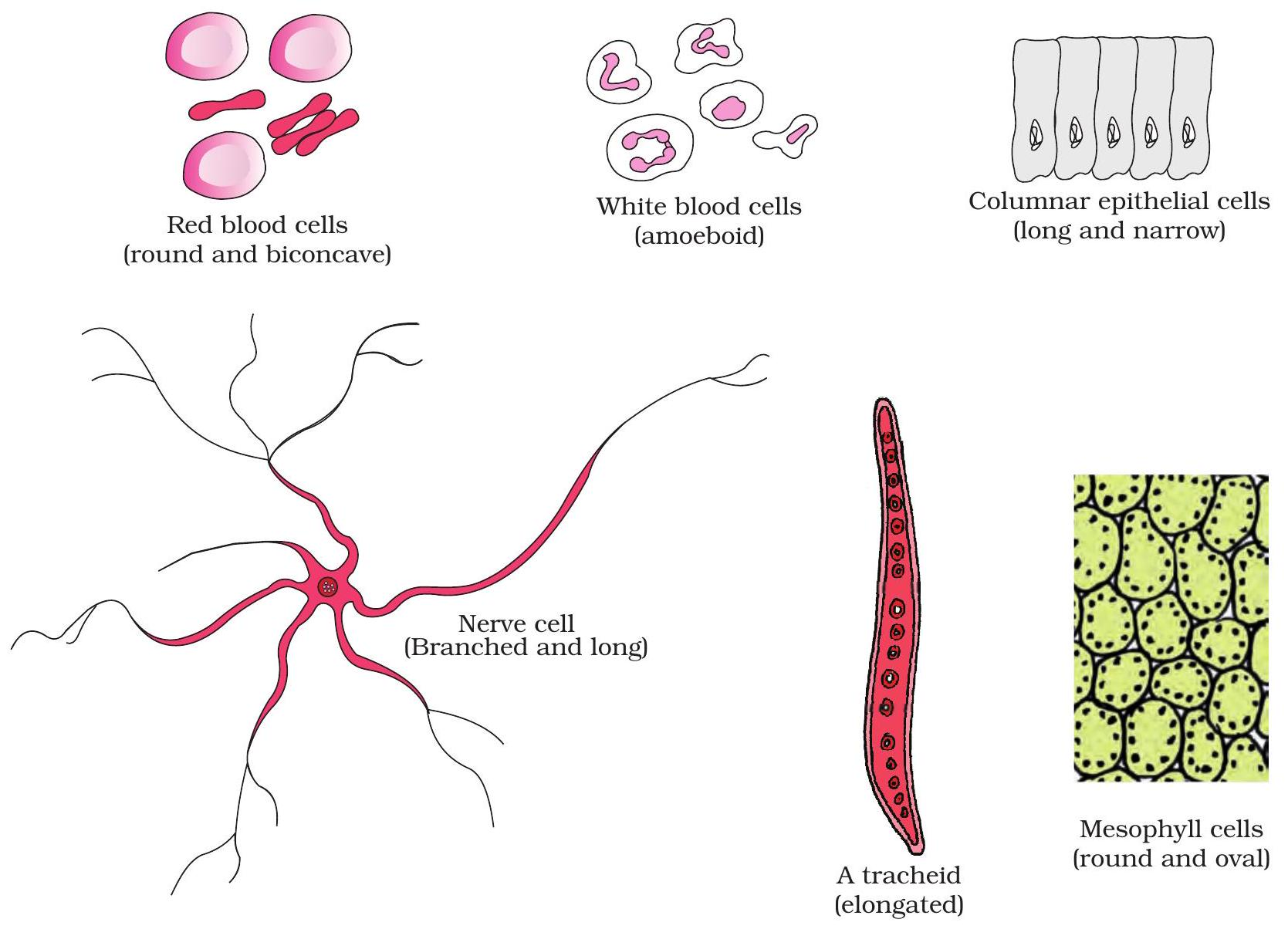

Shapes Tell Stories

Neuron & RBC illustrate how shape serves function.

Form Mirrors Function

Cell shapes evolve to match specific tasks, linking structure with performance.

Key Points:

- Neuron: Long, branched shape carries signals swiftly across the body.

- RBC: Thin biconcave disc increases surface area for rapid oxygen exchange.

- Muscle fibre: Cylindrical length lets contractile proteins slide for movement.

- Guard cell: Kidney shape opens or closes stomata to regulate gas flow.

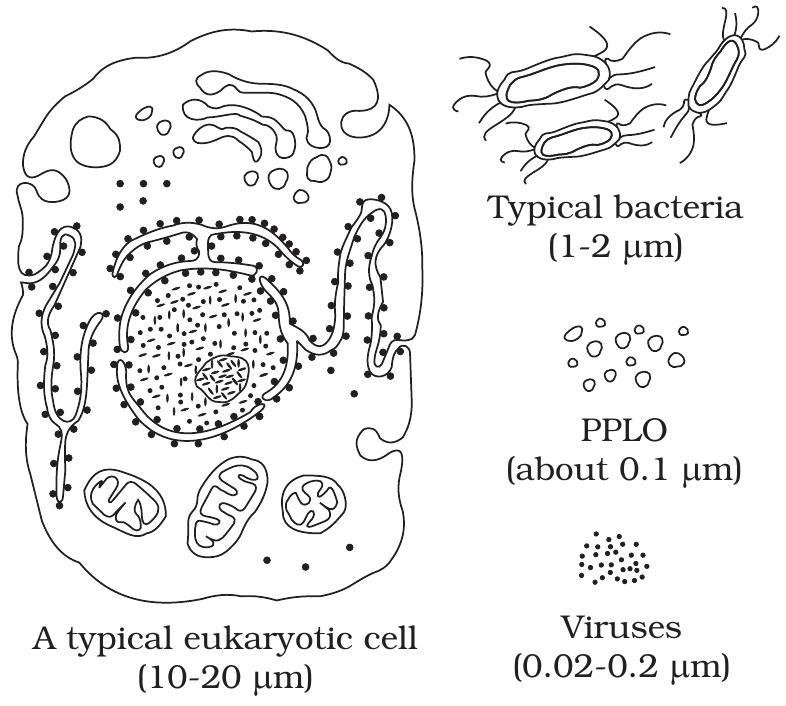

Sizing Up Cells

Relative sizes (not to scale)

Cell dimensions in μm

1 μm (micrometre) = 10⁻⁶ m; this unit sets the scale for cell biology.

Comparing sizes helps explain how surface area limits functions like nutrient uptake.

Key Points:

- Viruses: 0.02 – 0.3 μm, visible only with an electron microscope.

- Bacteria: 1 – 5 μm; typical prokaryotic size, light-microscope range.

- Eukaryotic cells: 10 – 20 μm; some specialised cells reach 100 μm.

Plant vs Animal Cell

Plant Cell

Animal Cell

Key Similarities

Which features are unique, and which reveal their common ancestry?

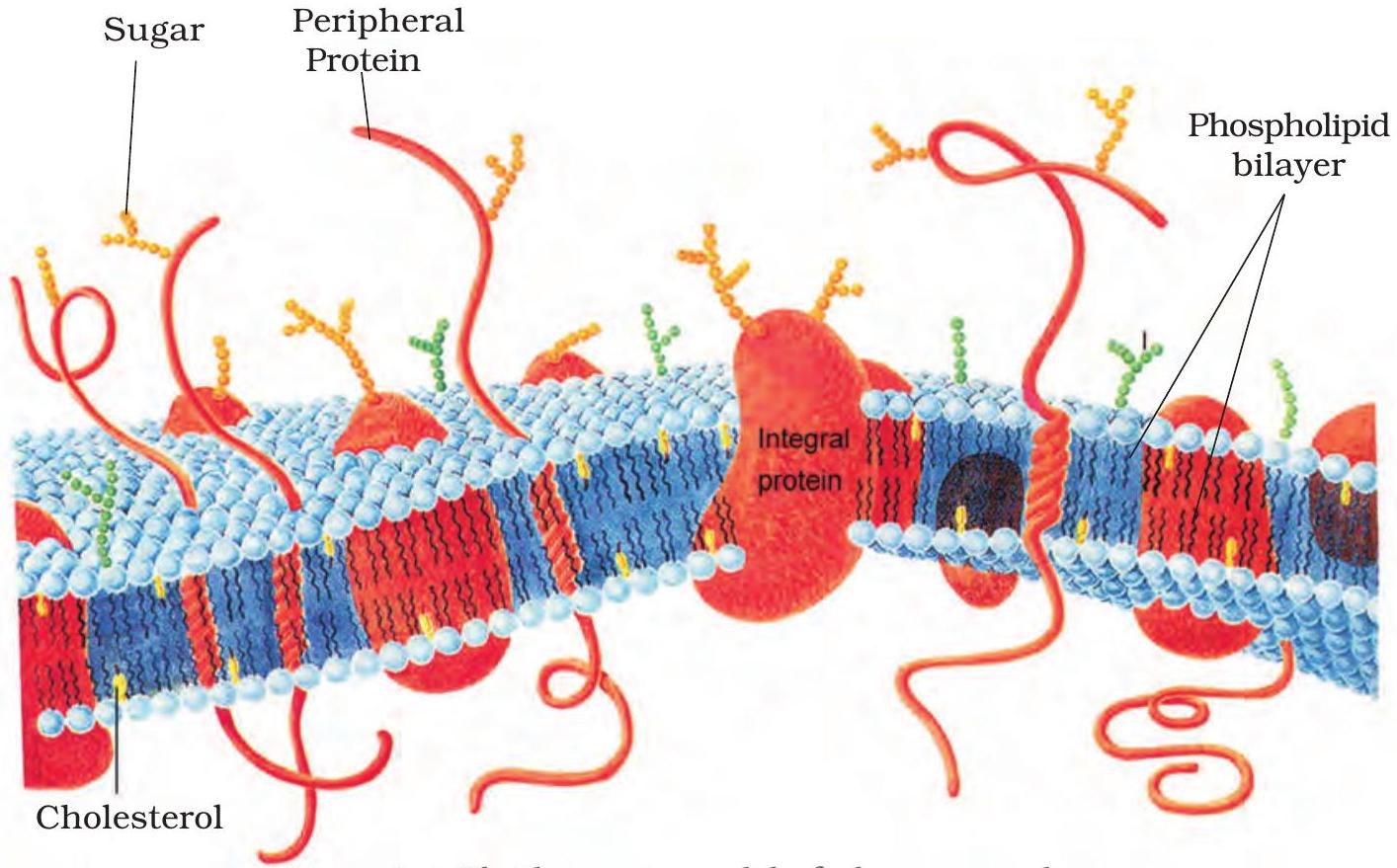

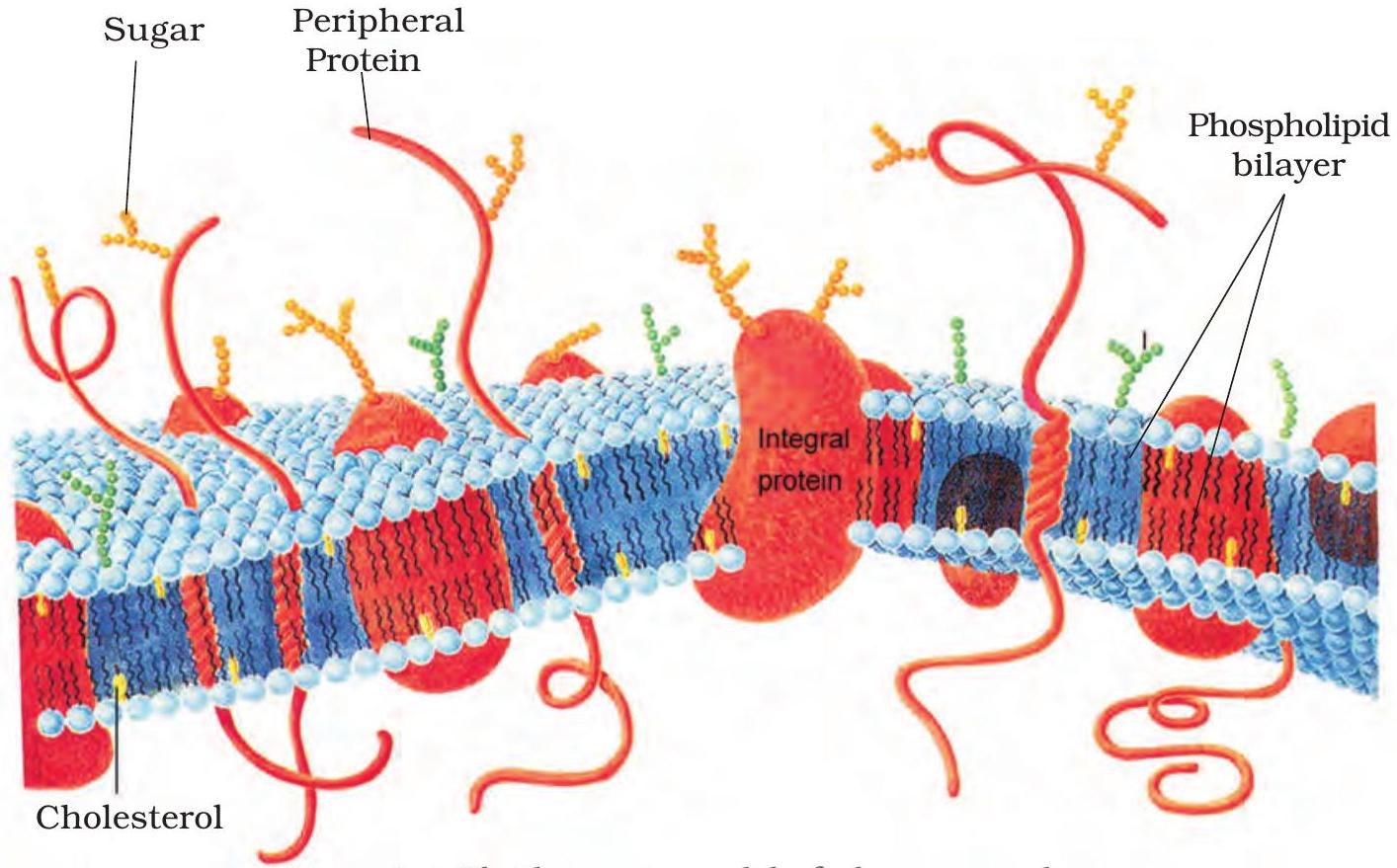

Fluid Mosaic Membrane

Fluid mosaic model (Singer & Nicolson, 1972)

Lipids drift, proteins skate

The plasma membrane is a fluid phospholipid sea that heals and flows.

Proteins move within this lipid matrix, creating the ever-changing mosaic.

Key Points:

- Phospholipids + cholesterol give flexibility and selective permeability.

- Proteins drift laterally but rarely flip between leaflets.

- Dynamic membrane explains cell growth, endocytosis, and self-repair.

Label the Membrane

Drag each label onto the correct feature of the plasma membrane diagram to show you can identify its components.

Draggable Items

Drop Zones

Phospholipid head

Hydrophobic tail

Integral protein

Peripheral protein

Cholesterol

Tip:

Remember: hydrophilic heads face water; hydrophobic tails hide inside the bilayer.

Results

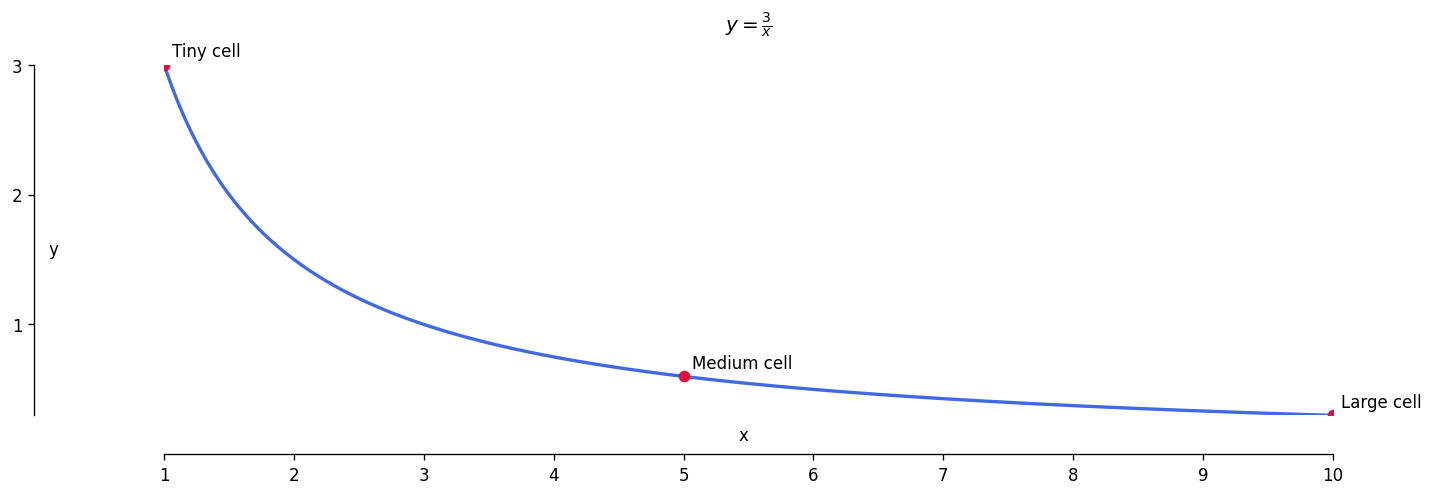

SA:V — The Maths

Surface area-to-volume ratio vs cell radius

Interpreting the Curve

For a sphere, \( \text{SA:V} = \frac{3}{r} \). Doubling radius halves the ratio.

The graph’s steep inverse drop shows how a slight size increase quickly lowers available surface for exchange.

Key Points:

- Inverse hyperbola: slope drops fastest at small radii.

- Lower SA:V limits diffusion-based nutrition and waste removal.

- Cells divide to regain a higher surface area-to-volume ratio.