What is an Ideal Gas?

Ideal Gas

Imaginary gas of point particles, no intermolecular forces, perfectly elastic collisions; therefore obeys \(PV=nRT\) at every \(T\) and \(P\).

Assumptions: molecules occupy zero volume, exert no attraction, and collide elastically. Average kinetic energy equals \(\tfrac{3}{2}k_{\rm B}T\); Boltzmann constant \(k_{\rm B}\) links single-molecule energy to temperature.

Pressure from Collisions

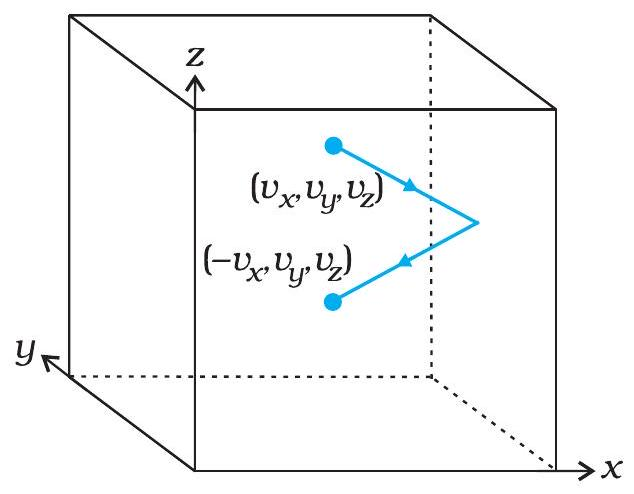

Molecule rebounds elastically from wall

How impacts create pressure

Gas molecules strike the wall in elastic collisions, reversing their normal velocity.

Each hit changes momentum by \(2 m v_x\) toward the wall.

The cumulative impulse of countless \(2 m v_x\) events per second manifests as steady gas pressure.

Key Points:

- Only \(v_x\) matters because the wall is perpendicular to the x-axis; \(v_y\) and \(v_z\) slide along the surface.

- Greater molecular speed or collision rate increases pressure.

Pressure Equation Build-up

One molecule hits the wall; its x-momentum reverses, giving change \(2m v_x\).

Collision rate is \(n A v_x/2\). Multiply by \(\Delta p\) to obtain force on the wall.

Pressure is force per area; still expressed with the x-component only.

Isotropy gives \(\langle v_x^{2}\rangle = \langle v^{2}\rangle/3\), inserting the missing \(1/3\).

Key Insight:

The factor \(1/3\) emerges because, in an isotropic gas, momentum and energy split equally among x, y, and z directions.

When Real Meets Ideal

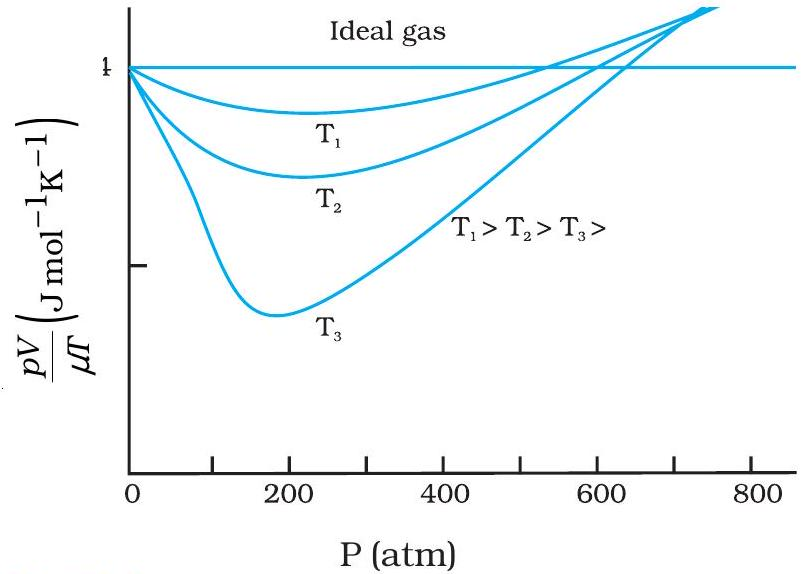

PV vs P curves for a real gas at three temperatures

Temperature tunes deviation

An ideal gas shows a flat \( PV \)-vs-\( P \) line; \( PV \) stays constant.

Experimental real-gas curves bend away from that line, marking deviation from ideal behaviour.

Higher temperature pushes molecules apart, so the curve flattens and approaches the ideal line.

Key Points:

- Ideal line: horizontal because \( PV = RT \).

- Real-gas curves dip then rise, revealing attractive and repulsive forces.

- Liquefaction is most likely along the lowest curve \( T_3 \).

Temperature ↔ Kinetic Energy

Equipartition: each degree of freedom carries \( \tfrac{1}{2} k_B T \) energy.

So absolute temperature fixes microscopic kinetic energy scale.

Variable Definitions

Applications

Explains why lighter gases move faster

For the same \(T\), smaller \(m\) gives larger \(v_{\text{avg}}\).

Basis for estimating stellar core temperatures

Observed particle speeds back-calculate \(T\) using \( \frac{3}{2} k_B T \).

Key Takeaways

Lock these in!

Gas ≈ Busy box of bullets

Pressure arises from countless molecular hits on walls; momentum change per second equals \(P A\).

PV ∝ T

For an ideal gas \(PV = nRT\); fix \(n\), any two variables determine the third.

T measures energy

Absolute temperature tracks mean kinetic energy: \(\frac{3}{2}kT = \langle \tfrac{1}{2}mv^{2}\rangle\).

Ideal vs Real

Model fails at high pressure or low temperature where intermolecular forces matter.

Test Your Insight

Question

At 300 K, which gas has the highest rms speed?

Hint:

\(v_{\text{rms}} \propto \frac{1}{\sqrt{M}}\)

Correct!

Yes—lighter atoms zip the fastest!

Incorrect

Check the molar masses; lighter means speedier.